- Brainwave Musings

- Posts

- Lauding a quiet life

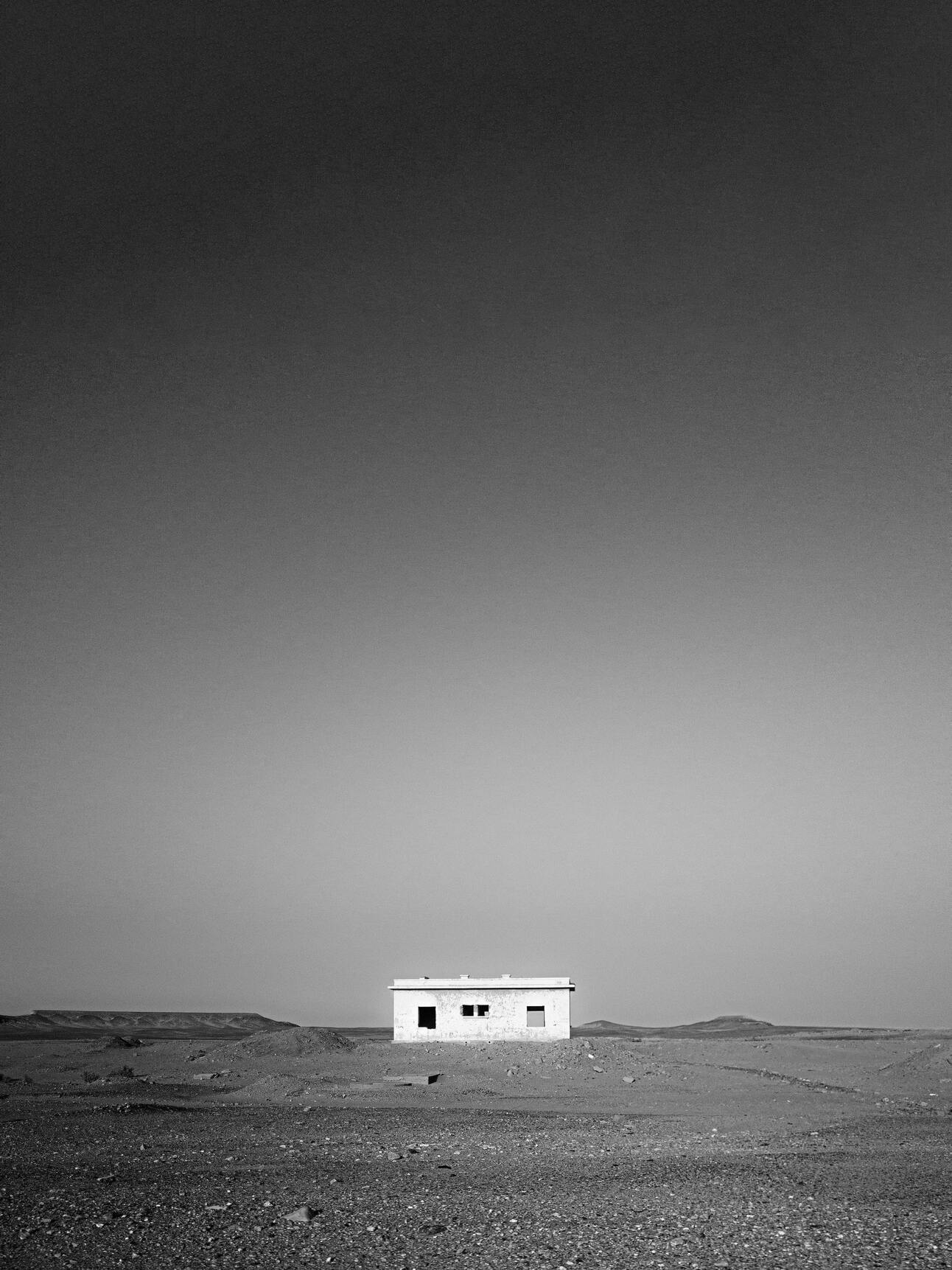

Lauding a quiet life

Praising a quiet life has the oddity of praising rain on a sunny day. It's a sentiment that, to many, seems to come only from those on the margins: the unemployed, the burned out, the overlooked, the ones who appear to have failed to "make it." In blunt terms—the poor!

There’s an insightful article I read way back, that goes a little something like this:

A quiet life sounds like an option that only the defeated would ever be inclined to praise.

Our age—this modern era of fast, hyper-connected, real-time technology—is overwhelmingly biased in favor of the loud, the dynamic, the ever-on-the-move. We celebrate the hustle. We idolize the grind. We chase the biggest salary, the loudest applause, the flashiest lifestyle. If someone offered us a better-paying job in a different city, we’d pack up and leave without a second thought. If a shortcut to fame opened up, we’d probably race down it. If someone invited us to a high-end party, we’d accept. Because all of these things seem, to most, like unambiguous victories and games.

In that context, praising a quiet life has the oddity of praising rain on a sunny day. It's a sentiment that, to many, seems to come only from those on the margins: the unemployed, the burned out, the overlooked, the ones who appear to have failed to "make it." In blunt terms—the poor.

The quiet life feels less like a lifestyle and more like something that happens to you when you have no other options. It’s what you’re left with when your talents don’t get you very far. And yet, when we pause and take a closer look, the glorified, busy lives we chase often come at surprising, and quietly devastating, costs.

First of all, time—the one currency we can never replenish—slips out of our hands. We have very limited control over it. Climb high enough in status and influence, and sure, you might be able to shut down a factory in Thika with a single phone call. Your words might carry the weight of law within your organization. But here's what you likely can't do: admit that you're exhausted. That you just want to lie on the couch for an afternoon with a cup of tea and a good book. That you're tired of pretending to be titanium when all you want is to be tender.

In such lives, our spontaneity shrinks. Our imaginations dry up. Our most vulnerable selves—the ones that laugh easily, cry freely, dream without shame—get locked behind the fortress of our curated lives.

Meanwhile, we become strangers to those who love us outside of our wealth and status. Our children see less of us. Our spouses turn distant and bitter. We may own houses in every province and drive cars that hum with luxury, but many of us can't remember the last time we sat still, did nothing, and felt joy in that stillness. Suddenly, Bruno Mars singing The Lazy Song doesn’t sound so silly anymore, it feels like an anthem.

One of the most famous figures in human history, a carpenter from Nazareth, was deeply interested in the quiet life. In the Good Book, Jesus sends out his disciples with radical instructions: take nothing for the journey—no bread, no bag, no money in your belts. Just a staff, sandals, and a single tunic. It was not deprivation. It was intentional living. Myself am a firm believer of minimalism, and a firm protestor against the tyranny of excess.

Christianity, in its deeper currents, offers a rare and valuable lens: it separates poverty into two kinds. There is involuntary poverty, yes—born of injustice, neglect, and systemic failure. But there’s also voluntary poverty, a conscious shedding of abundance in favor of something richer. Something eternal.

We, in our time, struggle to understand this. We treat all poverty as failure. As a lack of intelligence, a lack of ambition. We cannot imagine that someone might choose to walk away from money, from prestige, from power—not because they’re incapable of getting them, but because they’ve measured the cost, and it simply isn’t worth the price.

There are people, whether known to us or not, who have declined the promotion, refused the book deal, or walked away from a high-profile office—not out of weakness, but out of clarity. They want other things. Not lesser things—just quieter things. More meaningful things! They want time to notice the flowers in bloom, to study the teachings of Jesus, to rear rabbits in Karachuonyo, to honor the creator of the earth, to extend kindness to the hungry, the overlooked, and the forgotten.

The Chinese have long understood this. In their traditions, some of the wisest among them have walked away from the political, the commercial, the bustling and loud, to settle in humble huts carved into the side of mountains. There, they plant radishes, tend rice paddies, and fish with their children. Like Po and the Furious Five, finding their chi in the quiet rhythms of ordinary life.

And even us sometimes, when we finally reckon with the true cost of the careers we chase—the anxiety, the facades, the fear, the betrayal—we begin to see that perhaps, just perhaps, we aren’t willing to pay anymore.

Our days are limited on this earth. Some, who have tapped into the secrets of the universe, may for the sake of true riches, willingly and with no loss of dignity, opt to become a little poorer, and a little more… obscure.

✍🏽Reagan.